- Ridge Regression

- Why Ridge Regression performs better than least squares?

- The Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator)

- Is Lasso better than ridge regression?

- Selecting the Tuning Parameter

- Dimension Reduction Methods

- Principal Component Analysis

- The Principal Components Regression Approach

- Partial Least Squares

- Considerations in High Dimensions

- References

Ridge Regression

The least squares fitting procedure estimates $β_0$, $β_1$, …, $β_p$ using the values that minimize

$RSS = \sum_{i=1}^{n}(y_i-β_0-\sum_{j=1}^pβ_jx_{ij})$

Ridge regression is very similar to least squares except that the coefficients are estimated by minimizing a slightly different quantity. The ridge regression coefficient estimates $\hat{β}^R$ are the values that minimize

$\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i-β_0-\sum_{j=1}^pβ_jx_{ij})^2+\lambda\sum_{j=1}^{p}β_j^2=RSS+\lambda\sum_{j=1}^{p}β_j^2$

where λ ≥ 0 is a tuning parameter to be determined separately. As with least squares, ridge regression seeks coefficient estimates that fit the data well, by making the RSS small. However, the second term, $\lambda\sum_{j=1}^{p}β_j^2$ called as shrinkage penalty, is small when $β_1, …, β_p$ are close to zero, and so it has the effect of shrinking the estimates of $β_j$ towards zero. The tuning parameter λ serves to control the relative impact of these two terms on the regression coefficient estimates. When λ = 0, the penalty term has no effect, and ridge regression will produce the least squares estimates. However, as λ → ∞, the impact of the shrinkage penalty grows, and the ridge regression coefficient estimates will approach zero. Unlike least squares, which generates only one set of coefficient estimates, ridge regression will produce a different set of coefficient estimates, $\hat{β_λ^R}$, for each value of λ. Selecting a good value for λ is critical. It is also very important to apply ridge regression after standardizing the predictors so that they are all on the same scale.

Why Ridge Regression performs better than least squares?

The answer lies in bias variance tradeoff. As λ increases, the flexibility of the ridge regression fit decrease, leading to decreased variance but increased bias. In situations where the relationship between the response and the predictors is close to linear, the least squares estimates will have low bias but may have high variance due to which a small change in training data would cause a large change in the least squares coefficient estimates. When number of variables is almost as large as the number of observations, the least square estimates would be highly variable. If the number of variables is larger than the number of observations, then the least squares do not have a unique solution while ridge regression can perform well by trading off a small increase in bias for a large decrease in variance. So ridge regression works best in situations where the least squares estimates high variance.

The Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator)

The ridge regression shrinks all the coefficients towards zero but doesn’t make anyone of them as zero (unless λ = ∞). This creates problems in interpreting the model when the number of variables is high. The ridge regression always has includes all the predictors in the model. The lasso is a technique that overcomes this disadvantage of ridge regression. The lasso coefficients minimize the below quantity:

$\sum_{i=1}^n(y_i-β_0-\sum_{j=1}^pβ_jx_{ij})^2+λ\sum_{j=1}^{p}\vertβ_j\vert=RSS+λ\sum_{j=1}^{p}\vertβ_j\vert$

Comparing this with the ridge regression equation, it is seen that the $\vertβ_j\vert$ term replaces the $β_j^2$ penalty term. The lasso uses an $l_1$ penalty instead of an $l_2$ penalty which the ridge regression uses. The $l_1$ penalty forces some of the coefficient estimates to be exactly zero when the tuning parameter λ is large enough. As a result, the models produced by ridge regression are easier to interpret, so selecting a good value of the tuning parameter is important. When λ = 0, the lasso will generate a least square model but when λ is very large, the model would not contain any predictors.

Is Lasso better than ridge regression?

Neither of the methods universally dominates the other. The Lasso performs better when a small number of predictors have some substantial coefficients while the remaining predictors have coefficients that are very small or equal to zero. The Ridge Regression would perform better when the response is a function of many predictors, all of which coefficients are of equal size. Methods like cross-validation can be used to determine which approach is better on a particular data set.

Selecting the Tuning Parameter

Implementing ridge regression or lasso requires a method for selecting a value for the tuning parameter λ. A grid of λ values are chose and the cross validation for each value of λ is calculated. The tuning parameter for which the cross-validation error is smallest is selected. And finally, the model is re-fit using all the available observations and the selected value of the tuning parameter.

Dimension Reduction Methods

All the methods currently discussed controlled the variance in two ways, either by using a subset of the original variables or by shrinking their coefficients towards zero. All the methods are defined using the original predictors, $X_1, X_2,…, X_p$. A class of approach that transform the predictors and then fit a least squares model using the transformed variables is known as dimension reduction methods.

Let $Z_1, Z_2, …, Z_M$ represent M < p linear combinations of the original p predictors. That is

$Z_m = \sum_{j=1}^p\phi_{jm}X_j$

for some constants $\phi_{1m}, \phi_{2m}, …, \phi_{pm}, m=1, …, M$. We can then fit the linear regression model

$y_i=\theta_0+\sum_{m=1}^{M}\theta_mz_{im} + ε_i, i= 1,…, n$

using least squares. If the constants $\phi_{1m}, \phi_{2m}, …, \phi_{pm}$ are chosen well, then the dimension reduction approaches can often outperform least squares regression.

The term dimension reduction comes from the fact that this approach reduces the problem of estimating the p+1 coefficients $β_0, β_1,…, β_p$ to the simpler problem of estimating the M+1 coefficients $θ_0, θ_1,…, θ_M$ where M < p. So the dimension of the problem has been reduced from p+1 to M+1. With some mathematics, it can be deduced that,

$\sum_{m=1}^M\theta_mz_{im}=\sum_{j=1}^{p}β_jx_{ij}$

where $β_j=\sum_{m=1}^{M}\theta_m\phi_jm$

The above equation can be considered as a special case of the original linear regression model. Dimension reduction serves to constrain the estimated $β_j$ coefficients. The constraint on the form of the coefficients has the potential to bias the coefficient estimates. However, in the situations where p is large relative to n, selecting a value of M « p can significantly reduce the variance of the fitted coefficients. If M = p and all of the $Z_m$ are linearly independent, then the $β_j$ equation poses no constraints. In such a case, no dimension reduction occurs and so fitting a model is equivalent to performing least squares on the original p predictors.

All dimension reduction techniques work in two steps. First, the transformed predictors $Z_1, Z_2, …, Z_M$ are obtained. Second the model is fit using these M predictors. However the choice of $Z_1, Z_2, …, Z_M$ or the selection of the $\phi_{jm}$’s can be achieved using various methods. Principal component Analysis (PCA) and Partial least squares are two of the many such methods.

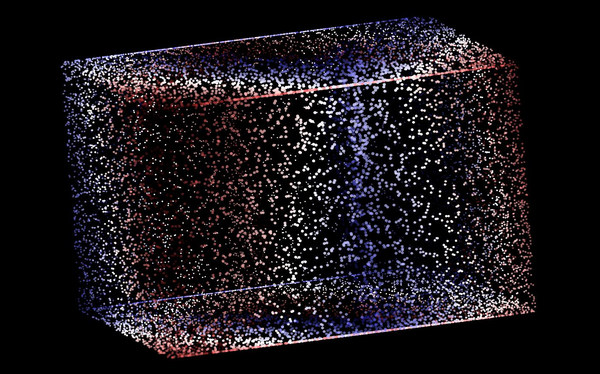

Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a popular approach for deriving a low dimensional set of features from a huge set of variables. PCA is a technique for reducing the dimension of a n x p data matrix X. The first principal component $(Z_1)$ direction of the data is that along which the observations vary the most. According to another interpretation of PCA, the first principal component vector defines the line that is as close as possible to the data.

p distinct principal components can be created. The second principal component $(Z_2)$ is a linear combination of the variables that is uncorrelated with $Z_1$ and has largest variance subject to this constraint. Its direction is orthogonal to the first principal component’s direction.

In general, for p predictors, most of the information would be contained in p principal components with of the information being present in the first, then the second, and so on.

The Principal Components Regression Approach

The principal components regression (PCR) approach involves constructing the first M principal components $Z_1, Z_2,…, Z_M$ and then using these components as the predictors in a linear regression model that is fit using least squares. The key idea behind this is that often a small number of principal components suffice to explain most of the variability in the data, as well as the relationship with the response. In short, its assumed that the directions in which $X_1,…, X_p$ show the most variation are the directions that are associated with Y. While this assumption is not often true, but it turns out to be a reasonable enough approximation to give good results.

But just the first principal components isn’t always enough to give good results. So few other principal components need to be used and the number of principal components is given out by cross validation. Even though PCR gives a simple way to perform regression using M < p predictors, it is not really a feature selection method. This is because, the M components used in the regression is a linear combination of all of the p original predictors.

It is also advised that each of the predictors must be standardized prior to generating the principal components. In the absence of standardization, the high variance variables will tend to play a larger role in the principal components obtained and the scale on which the variables are measured will finally affect the PCR. Standardization ensures that all the variables are on the same scale. However, if all of the variables are measured in same units (years, pounds, inches, etc) then standardization is not necessary.

Partial Least Squares

The PCR approach involves identifying linear combinations or directions that best represent the predictors. These directions are identified in an unsupervised way since the response is not used to help determine the principal component directions or in another word, the response doesn’t supervise the identification of the principal components. So, PCR suffers from a great drawback i.e. there is no guarantee that the directions that best explain the predictors would also be the same directions to predict the response.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) is a supervised alternative to PCR. It makes use of the response to identify new features that are not only approximate the old features well but also are related to the response. So PLS approach attempts to find directions that help explain both the response and the predictors.

In PLS, after standardizing the p predictors, PLS computes the first direction $Z_1$ by setting each $\phi_{j1}$ in the above-mentioned equation equal to the coefficient from the simple linear regression of Y onto $X_j$. This coefficient is proportional to the correlation between Y and $X_j$. So in computing $Z_1 = \sum_{j=1}^{p}\phi_{j1}X_j$, PLS places the highest weight on the variables that are most strongly related to the response.

To identify the second PLS direction each of the variables need to be adjusted for $Z_1$ by regressing each variable on $Z_1$ and taking residuals. These residuals can be interpreted as the remaining information that has not been explained by the first PLS direction $Z_2$ is then computed using this orthogonalize data in the same way $Z_1$ was computed based on original data. This method can be repeated M times to get the multiple PLS components $Z_1$,…, $Z_M$. Finally, at the end of the procedure, a least squares is used to fit a linear model to predict Y using $Z_1$,…, $Z_M$ on the same lines as PCR.

The number M of partial least squares directions used in PLS is a tuning parameter that is typically chosen by cross validation. The predictors and response need to be standardized before performing PLS.

Considerations in High Dimensions

High Dimensional Data

Most traditional statistical techniques for regression and classification are intended for the low-dimensional setting in which the number of observations (n) is much greater than the number of features (p) as most of the scientific problems requiring the use of statistics are low dimensional.

As a simple example, if a model is built to predict a person’s blood pressure on the basis of his/her age, gender and body mass index (BMI), then thousands of patient’s information is available for whom all these data is available. Here n » p, so this is a low dimensional.

But over the last few decades, modern technologies have emerged where unlimited number of features can be collected though the number of observations is limited due to cost factor, sample availability and other considerations.

For e.g. for predicting blood pressure half a million of SNP (single nucleotide polymorphisms that are individual DNA mutations which are common for population) can be collected and included in the model.

As another example, a marketing analyst interested in understanding customer’s online shopping patterns can treat the search terms entered in the search engine as features (bag of words model). The analyst can have thousands of user’s search information where p search terms are either present or absent creating a large feature vector.

Such data sets where number of features are more than the number of observations are referred as high dimensional data. Classic approaches like least squares linear regression is not suitable for these cases due to the bias-variance trade off and the danger of overfitting.

What goes wrong in High Dimensions?

Least squares cannot be applied to high dimensional data as regardless of whether or not there is truly a relationship between the features and the response, least squares will always yield a set of coefficients estimates that result in a perfect fit to the data where residuals are zero. The model will perform poorly for the test set and hence won’t be useful. $R^2$ would increase as the number of features increase and training MSE would decrease to 0 even though the features are completely unrelated to the response. Test MSE on the other hand would be really large as the number of features in the model increases as addition of new predictors lead to vast increase in the variance of the coefficient estimates.

Approaches to adjust the training set RSS or $R^2$ in order to account for the number of variables used to fit a least square model ($C_p$, AIC, BIC) are not appropriate in the high dimensional setting. Adjusted $R_2$ is also not suitable to use in high dimensional setting as a model with adjusted $R_2$ value of 1 can be easily obtained.

Regression in High Dimensions

Forward stepwise selection, ridge regression, lasso and PCR are useful in performing regression in the high dimensional setting as they avoid overfitting by using a less flexible fitting approach than least squares. In general

- Regularization or shrinkage plays a key role in high dimensional problems

- Appropriate tuning parameter is essential for good predictive performance

- Test error tends to increase as the number of predictors increases, unless the additional predictors are truly associated with the response, also known as curse of dimensionality

Hence the modern technologies that allow for the collection of measurements for thousands or millions of features are a double-edged sword as they can lead to improved predictive models if these features are in fact relevant to the problem at hand but will lead to worse results if the features are not relevant. Even if they are relevant, the variance incurred in fitting their coefficients may outweigh the reduction in bias that they bring.

Interpreting Results in High Dimensions

When ridge regression, lasso or any another regression procedure is performed in high dimensional setting, reporting the results must be done in a cautious manner. In high dimensional setting, the multicollinearity problem exists where any variable in the model can be written as a linear combination of all of the other variables in the model. So its never possible to know exactly which variables are truly predictive of the outcome and the best coefficients predictive of the outcome are never known.

For e.g. in the prediction of blood pressure based on half million SNPs, if any variable selection method indicate 17 SNPs lead to good predictive model on the training data, then its incorrect to conclude that only these 17 SNPs predict blood pressure and not any of the excluded SNPs. If another dataset is obtained and the same variable selection method is performed then its highly probable that another set of SNPs would be obtained. The SNPs obtained can be effective in predicting blood pressure on the data set and be useful to physicians but the results should not be overstated. Its simply one of the many possible models for predicting blood pressure and should be validated against other independent data sets.

Reporting errors and measures of model fit in high dimensional setting should also be done with proper care. Sum of squared errors, p-values, $R^2$ statistics or any other traditional measures of model fit on the data should never be used. Doing so would mislead into thinking that a statistically valid and useful model has been created. Results on independent test sets or cross validation errors should instead be reported.

References

- James G., Witten D., Hastie T., Tibshirani R. (2013). An introduction to Statistical Learning. New York, NY: Springer

This article is written by ashmin Follow him @ashminswain.